Here we go again. Details here. Please leave comments about anything you want and I’ll do my best to give thorough responses.

Getting DirecTV Monday but having to wait until today to use Sunday Ticket has been like waiting to open a Christmas present I bought myself.

10:00: Tough to pick a game with the Panthers, Lions, Steelers, and Bills games all having surprisingly interesting story-lines, so I’m going to stick with the Red Zone Channel for a few.

10:07: OK, I didn’t know this was humanly possible, but I think RZC is too ADD for me, so I’m going to switch to the Panthers game.

10:11: I wonder what qualities on teams are most likely to lead to successful rookie campaigns. And given that successful rookie campaigns tend to fizzle out in future years, do those same things perhaps correlate negatively with long-term success?

10:18: Ugh, breast cancer awareness. Am I the only one that finds the breast cancer pandering to be a little insidious? It’s politically an easy cancer to go with, and has cross-gender appeal, but it’s already over-funded relative to its prevalence and mortality rates. See this slightly out-of-date NYTimes article: Lung Cancer receives $1,630 research dollars per death, and Breast Cancer receives $13,452.

Maybe lung cancer is politically toxic b/c it’s seen as the smoker’s curse, but Colon cancer kills more people and gets 1/3 the funding. But it wouldn’t be nearly as sexy to wear brown “Colon Cancer Awareness” ribbons.

10:25: Ok, 20 minutes and no graphs, I know, derelict.

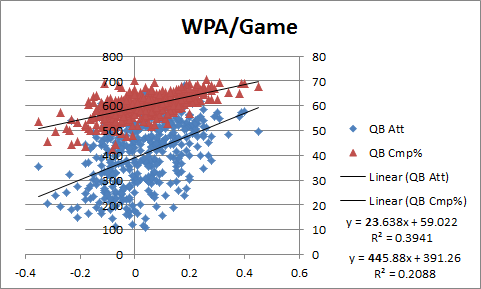

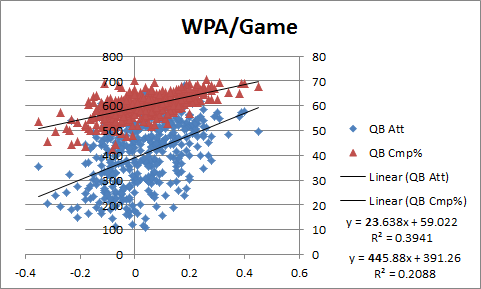

10:35: Ok, this was an idea that turned out approximately how I expected. This is Win Percentage Added per Game on the X-axis and Attempts and Completion percentage on the Y-axes:

The interesting part is that attempts has a higher relative slope, but completion percentage has a better R-squared. In other words, completion percentage is more reliable, but less indicative.

10:42: Google search that just led to the blog: “should I start Michael Vick over Cam Newton today.” Welcome, fantasy footballer! And sorry, I have no idea. I don’t play fantasy football anymore: it’s pleasantly time consuming and has near-infinite depths for analysis, but the overlap with analysis of things that matter is way too small.

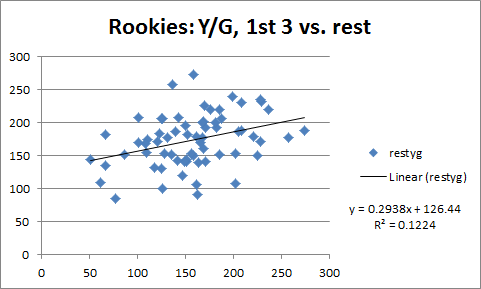

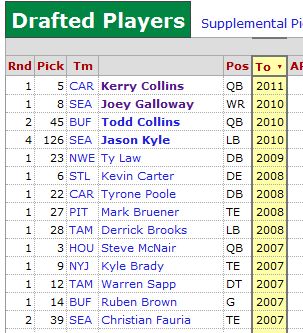

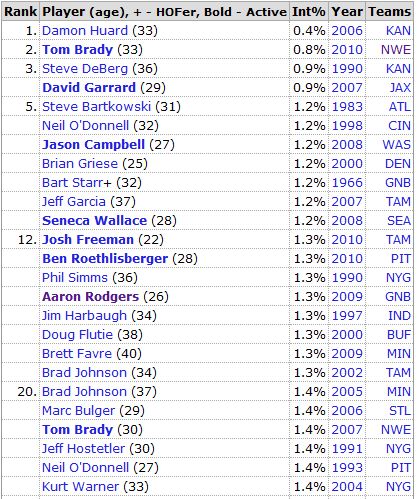

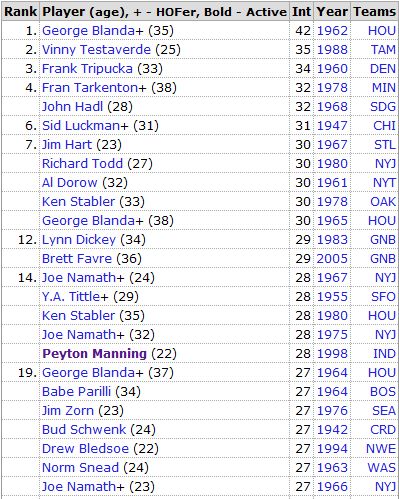

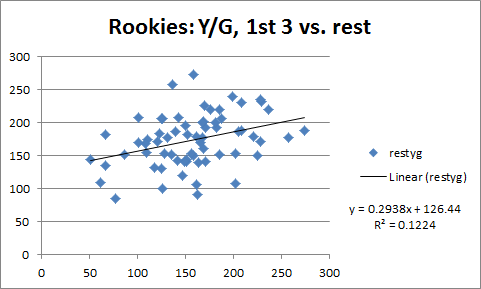

11:02: More on Cam Newton. Here’s rookie QB’s YPG over their first 3 starts vs. their YPG for the rest of the season (min 8 starts total):

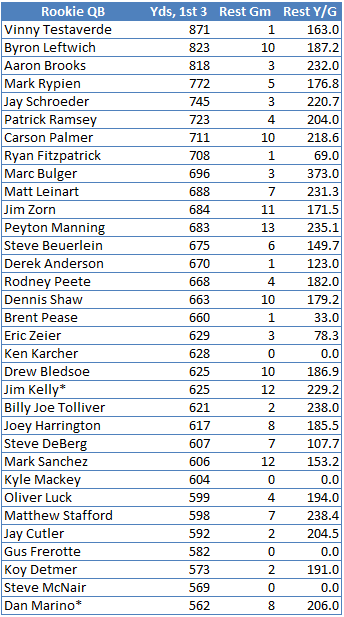

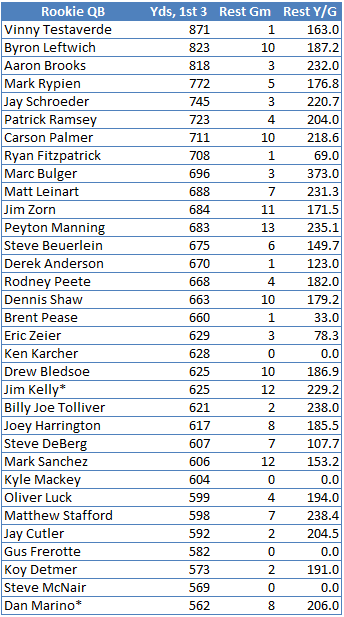

11:18: Here’s the table of rookies through Dan Marino (who I thought would have been higher):

Cam Newton, of course, has 1012 through his first 3. And in game 4 he has already passed Vinny Testaverde’s production for the rest of his rookie season.

11:22: Oops, I apologize. The above counts games played by rookie quarterbacks, not just games started.

11:30: Reliable blog-fan Matt comments:

I’m watching Redskins-Rams right now, and they just called a personal foul on a punt coverage player for “hitting a defense-less receiver,” as he pummeled the punt returner just as the returner caught the ball. He did not hit him prior to the ball being caught.

Now, I’m sure the officials are properly applying the rule. But this has to be a dumb rule, right? This is why we have the fair-catch rule. To me, as long as the hit is clean (i.e. not helmet-helmet, etc.) and you don’t hit him prior to him touching the ball, this rule is unnecessary. (Note that this is different than hitting a defenseless receiver on a pass play over the middle; he can’t declare (or not declare) a fair catch.

I didn’t see the play, but I’m not sure I entirely agree, at least as a theoretical matter. I can imagine there being a scale for how “unnecessarily rough” a hit is relative to how defenseless the target is. But, yes, I agree that there is a bit of discord between this approach and the fair catch rule, which is basically a completely objective but much more crude way of addressing the same issue.

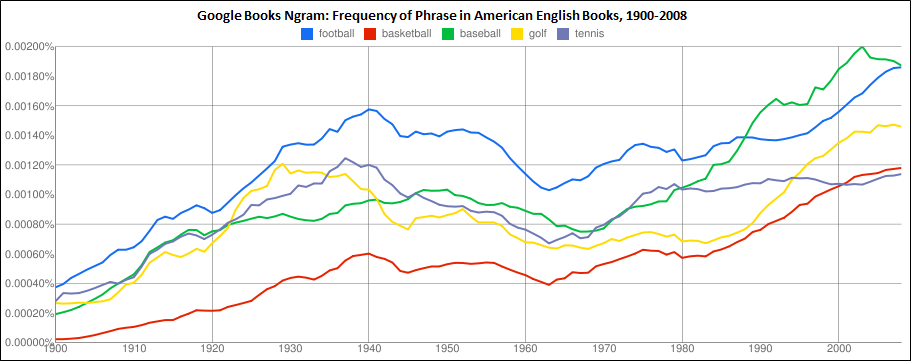

11:35: Broadly, I think the league is moving away from the “brutality” of violence and more toward the “finesse” of passing. I imagine that (in addition to protecting the players, blah, blah) they think they’re giving the fans what they want. But I don’t know. As an aesthetic matter, I think people are more mesmerized by the “finesse” side of the game, but possibly without realizing that a good chunk of its beauty comes from the contrast.

11:39: Ok, getting long enough that I’m switching to the split format that seemed to work last week.

11:50: A friend on IM:

Friend [11:40 AM]: i think people realize they like the contrast

Friend [11:40 AM]: i doubt there are numbers for it, but i’ve heard anecdotes about training camp attendance

Friend [11:41 AM]: and how it sharply increases when full pads

I at least partly agree. The typical fan knows that they like the violence, though I’m not sure they understand how the two sides enhance each other. And I’m not sure that the league understands this either. I think they probably see it a matter of addition: for example, say it used to be 40 utils of pleasure from finesse and 40 utils of pleasure from violence, for 80 total. They believe that if they can sacrifice 20 utils of violence for 25 of finesse, they’ll have upped the total utility to 85. But if the total aesthetic utility corresponds to the product of the two values, they would have actually reduced the value from 1600 (40*40) to 1300 (65*20).

12:09: Matt asks:

Anyway, I wanted to pose you a question regarding time management. Skins complete pass on 2nd down, setting up 3rd and 2, from their own 28, with about 1:20 to play. Neither team calls a timeout. That could very well be correct, but I assume similar situations are ripe for poor decision making. (i.e. if it’s 3rd and 17, Rams definitely call TO; if the ball is at the 48, Skins probably call timeout). Any thoughts / empirical work you’ve done/seen on this?

Yes, I’ve looked into it some. The situational analysis is sticky and hard to generalize, but the main thing to note is that any time it has a significant effect, one of the two teams will usually have the incentive to take the timeout, at least somewhere within the given sequence of downs (unless the value of keeping it is greater).

In this situation, the Redskins gain little by taking the timeout, since letting the clock run down and keeping it for later is virtually equivalent with 1:20 left, the marginal difference to their scoring chances isn’t huge, and the bigger risk to them is giving St. Louis too much time. Conversely, the Rams prob should take it. Take a look at this old link about two minute drills for some relevant stats.

12:29: Random stat from my PBP database: For home teams, 19% of drives starting with a kickoff end in a touchdown, for away teams, just under 17%.

12:39: But on the first drive of a game, home teams score TD’s on 22%, away teams just 16%.

12:56: Sorry I’m so slow this morning. It’s not slacking, I’ve been playing around with some PBP data relating to Matt’s question above, and any time I start wading through PBP stuff, I get easily distracted. There’s something new and fascinating around every corner!

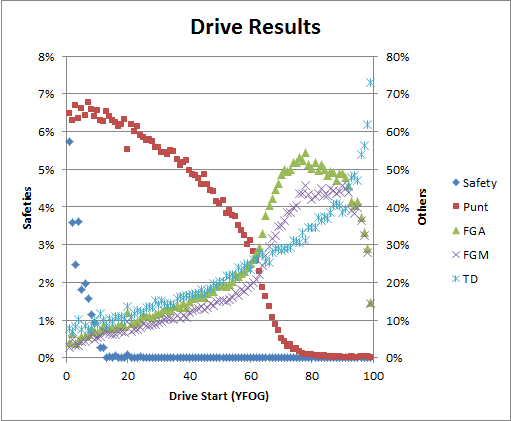

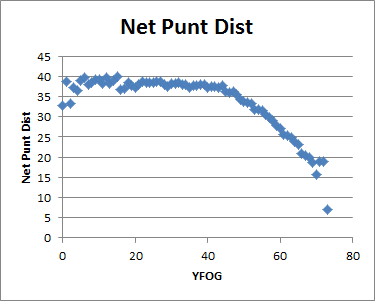

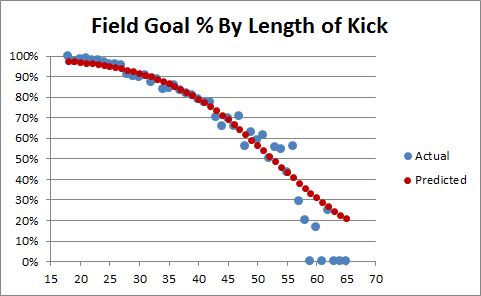

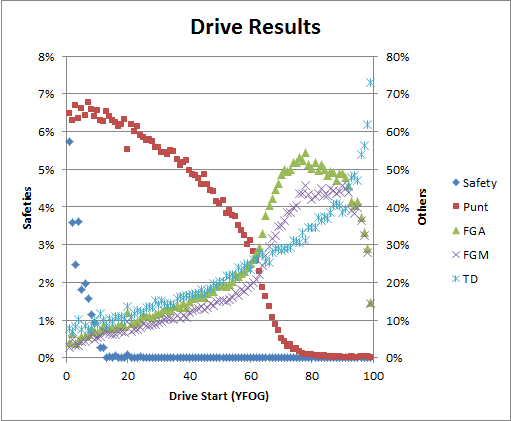

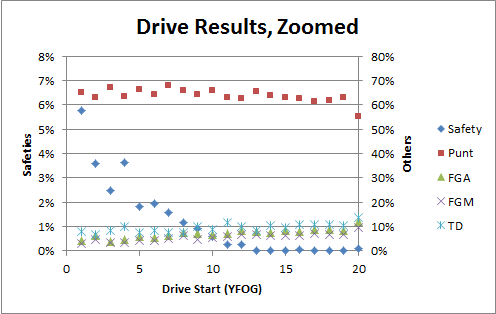

1:11: OK, here’s what should be considered a pretty basic graph, but it has some interesting subtleties to it:

Comment to follow.

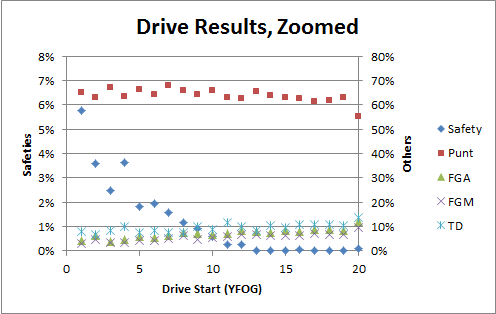

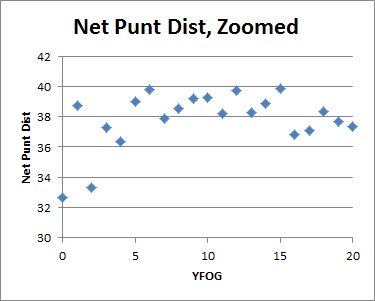

1:24: One of the interesting things about this graph is what’s going on in the first 20 yards:

So what’s interesting about this? Well, that aside from safeties, these particular results are very linear. I think many people would expect that being backed into your endzone makes executing your offense a lot harder — but aside from the occasional safety, the outcomes are really no worse than what you would expect from just being more yards back (turnovers aren’t shown b/c of data mashing issues, but there’s not a massive jump for them either).

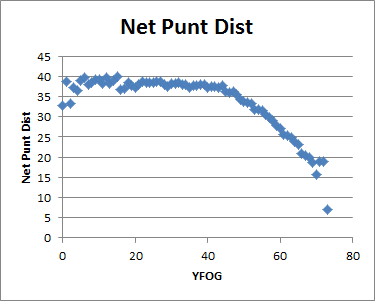

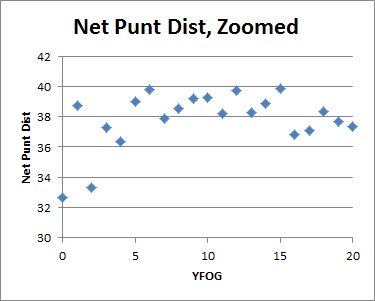

1:35: Of course, the other important factor:

And, the corresponding graph limited to your own 20:

1:41: Grabbing lunch, back in a few.

1:44: Bill Simmons tweets:

sportsguy33

The Cowboys really need to fire Wade Phillips. This has dragged on far too long.

20 minutes ago

Ha! I Think the NFL Coach with the longest tenure at the moment is Jerry Jones Puppet X.

2:09: So the take-homes from the above graphs are that the situation gets significantly better/worse within the 5 yard line, accelerating as you approach the goal line. This is why kicking field goals from the 1 is terrible even in situations where it has some tactical benefit. Obv this is nothing new to anyone even slightly informed about “expected value” in football (it’s basically the prototypical example), but to break it down clearly: If you don’t score on your 4th down play, trapping your opponent in that spot is valuable 4 ways:

- Natural field position advantage vs. giving your opponent the ball on the 20 after a made field goal.

- Significantly increased chance of a safety.

- Increased chance of good field position b/c of short opponent punts.

- Your subsequent field position also starts to hit the increasing part of your Touchdown/Expected Points curve (i.e., it has value in addition to the generic value of better expected field position).

Though it should be noted that the last 3 effects are much stronger on the 1 than on the 5.

2:16: After Red Zone Channel-ing it for a while, I’m switching to the New England game.

2:17: This is odd: Traffic for the live blog is up from last week, but commenting is down. Come on, people!

2:25: So these Sunday Ticket “Short Cuts” are pretty sweet: They’re 30 minute versions of each game that include every play and no filler. But their utility is limited by the fact that they just cut up the original sound track and don’t have any new commentary or any other way of identifying who is involved in each play: About half the time, the commentators get cut off before saying who the runner or receiver was. At the very least, they should scroll the play-by-play along the bottom.

Also, while it might make the vids slightly longer, they should take at least a moment to dwell on the particularly big or important plays: It’s weird when there’s like a 60 down touchdown pass, then bam!, extra point, kickoff, etc. Show a few replays! Not only is it more fun that way, but they contain important information.

2:51: Random thought: There’s a pretty simple pattern of where analytics has and hasn’t been adopted in sports: it has been adopted in spots where decision-makers can blame other people for having been wrong all along, and it hasn’t been adopted in places where decision-makers would have to blame themselves.

2:59: Congrats to the Lions, but with apologies to Nate, there’s at least one good reason to root against Detroit: If they end up going to—or, god forbid, winning—the Super Bowl, the stories about the recession/auto industry recovery and the Lions being the main source of hope for a struggling community, etc., may be even more insufferable than the litany of identical stories we had with New Orleans.

3:12: More on the “random thought” above: So the sport of baseball has no problem with the Moneyball movie, I’m sure, b/c who are portrayed as the stupid ones: The nameless, decrepit, curmudgeonly old scouts in the basement? The faceless, nameless, obnoxious talk radio hosts and listeners? The only baseball execs we see are 1) the Oakland ownership, who tell Beane to do what he’s got to do, 2) the Cleveland management, who, for some unknown reason, listen to this lackey analyst that they supposedly disrespect, and 3) the glorious, heartwarming Red Sox. Even the “clueless” manager really only has one major dispute: whether to start Peña (an All-Star) or Hatteburg at 1st base, which is ultimately portrayed as a near-push anyway.

3:19: And within the sport of Baseball, look at where analytics has been most embraced: 1) Player evaluation—something it is easy to blame others for (as above). And 2) High-granularity pitching and batting stats (location, etc), which are just an advancement in technology, and not having them before was no-one’s fault. And where has it been rejected and ignored? Strategic decisions! Teams still steal too much, bunt too much, they’re still stuck on archaic pitching rotation strategy (e.g., Mariano Rivera should either be pitching more innings or more important innings: the way he is used is demonstrably inefficient), etc. And who is responsible for having gotten those wrong for so long? The same people who are in position to accept or reject new approaches!

3:43: So the most exciting game going atm is Giants/Cardinals—ugh. I did mention I’ll try to answer almost any question, right? Aren’t there any Dennis Rodman haters out there who can give me something more interesting to talk about than Eli Manning’s mediocrity?

3:46: Even with the New England’s defensive problems, I think my generic “Patriots vs. Whoever Was The Best Team in the NFC Last Season” Super Bowl pick is looking pretty decent right now.

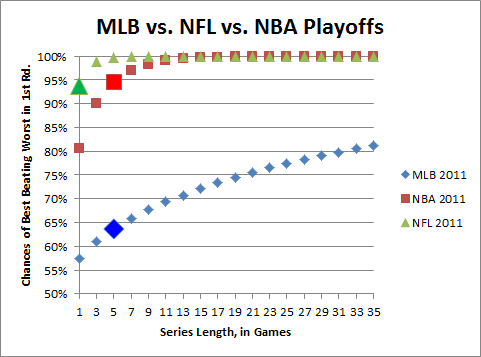

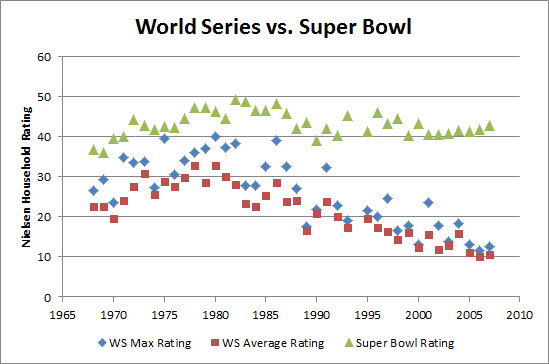

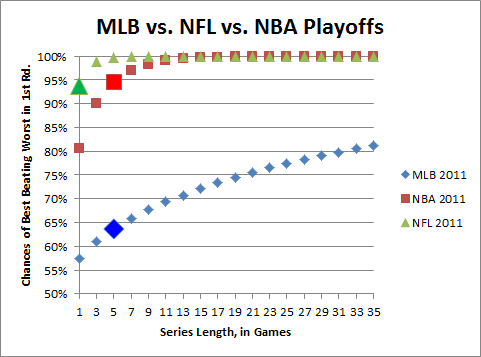

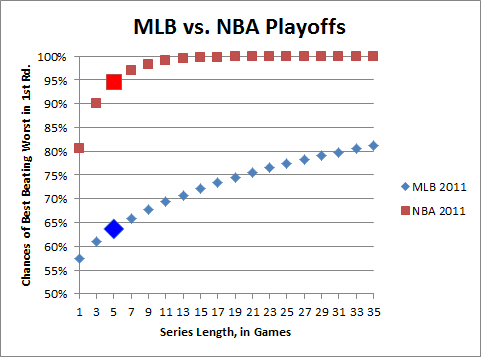

4:16: In support of last night’s screed, especially the claim that “[MLB] games are either not important enough to be interesting (98% of the regular season), or too important to be meaningful (100% of the playoffs),” here’s a graph I made to illustrate just how silly the MLB Playoffs are:

4:30: Not counting home-field advantage (which is weakest in baseball anyway), this represents the approximate binomial probability of the team with the best record in the league winning a series of length X against the playoff team with the worst record going in. The chances of winning a game are approximated by taking .5 + better win percentage – worse win percentage (note, of course, the NFL curve is exaggerated b/c of regression to the mean: a team that goes 14-2 doesn’t won’t actually win 88% of their games against an average opponent. But they won’t regress nearly enough for their expectation to drop anywhere near MLB). The brighter and bigger data points represent the actual 1st round series lengths in each sport.

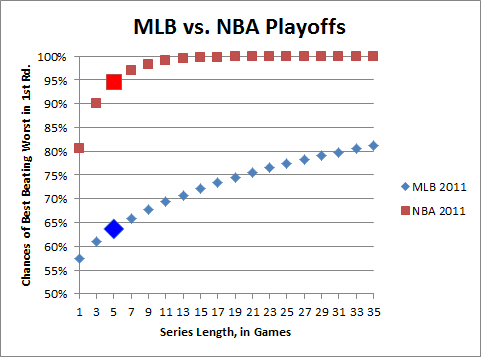

By this approximation, the best team against the worst team in a 1st round series (using the latest season’s standings as the benchmark) in MLB would win about 64% of the time, while in the NBA they would win ~95% of the time. To win 2/3 of the time, MLB would need to switch to a 9 game series instead of 5; and to have the best team win 75% of the time, they would need to shift to 21 (for the record, in order to match the NBA’s 95% mark, they would have to move to a 123 game series. I know, this isn’t perfectly calculated, but it’s ballpark accurate). I like the fact that the NBA and NFL postseasons generally feature the best teams winning.

Moreover, in a sense, it also makes upsets more meaningful: since the math is against “true” upsets happening often, an apparent upset can be significant: it often indicates—Bayes-wise (ok, if that’s not a word, it should be)—that the upsetting team was actually better. In baseball, an upset pretty much just means that the coin came up tails.

4:42: Adam asks:

In the MLB vs. NFL vs. NBA Playoffs graph, the chances of best beating worst in first round for NFL for a 1 game series is almost 95%.

Looking at the odds to this week’s NFL games, the biggest favorite was GB verses Denver and they were only an 88% chance of winning by the money line (-700). Denver is almost certainly not a playoff team, so it’s tough to imagine an even more lopsided playoff matchup that could get to 95%. What am I missing?

I sort of addressed this in my longer explanation, but you’re not missing anything: the football effect is exaggerated (but the reality still doesn’t drop anywhere near baseball). First off, to your specific concern, this early in the season there is even more uncertainty than in the playoffs. But second, and more importantly, this method for approximating a win percentage is less accurate in the extremes, especially when factoring in regression to the mean (which is a huge factor given the NFL’s very small sample sizes). Maybe I’ll update the math tonight or tomorrow, but even this crude demonstration should be sufficient proof of the point.

4:52: In fact, the regression to the mean effect in the NFL is SO strong, that I think it helps explain why so many Bye-teams lose against the wild-card game winners (without having to resort to “momentum” or psychological factors for our explanation). By virtue of having the best records in the league, they are the most likely teams to have significant regression effects. That is, their true strength is likely to be lower than what their records indicate. Conversely, the teams that win in the bye week (against other playoff-level competition), are, from a Bayesian perspective, more likely to be better than their records indicated. Think of it like this: there’s a range of possible true strength for each playoff team: when you match two of those teams against each other (in the WC round), the one who wins might have just gotten lucky, but that particular result is more likely to occur when the winning team’s actual strength was closer to the top of their range and/or their opponent’s was closer to their bottom.

In fact, I’ve looked at this before, and it’s very easy to construct scenarios where WC teams with worse records have a better projected strength than Bye teams with better records. Factor in the fact that home field advantage actually decreases in the playoffs (it’s a common misconception that HFA is more important in the post-season: adjusting for team quality, it’s actually significantly reduced—which probably has something to do with the post-season ref shuffle: see section on ref bias in this post), and you have a recipe for frequent upsets.

4:55: In retrospect, I probably should have just left the NFL out of that graph. Basketball makes for a much better comparison:

4:59: Arturo tweets:

ArturoGalletti

Safe to say at this point, Phillip Rivers is << than Drew Brees

Man, it’s like I KNOW Brees is awesome, sort of, but I still have lingering doubts that a 6-foot tall QB can really be that good. I mean, I feel like a bigot, but I’ve looked at the math over and over again, and he’s such a massive outlier that I can’t let it go.

5:11: WTF? With the latest Firefox update, I can no longer drag tabs left and right. Did Mozilla hire the Netflix web design team or something?

5:12: “Don’t kick it to Devin Hester.” Man, can we please retire this stupid observation? He has 12 return touchdowns. In 6 years.

5:32: Ok, I’m not finding the 12 number they’re mentioning, but Hester has 11 TD on 182 punt returns and has averaged 12.6 yards per return. This is obviously excellent, but please: the average punt return is 8.1 yards. What is the cost of punting away from Hester? It’s not like this is a free proposition. Hint: it’s probably more than 4.5 yards. And you know who else scores touchdowns? Teams with better field position.

5:37: I hate the new Facebook. I mean, I wasn’t the biggest fan before. But it’s like they took every thing I hated about it and multiplied them each by 10. Unrelatedly, don’t forget sign up for updates on the Skeptical Sports Analysis Facebook page!

5:41: I think I’m addicted to scatterplots. <— new contender for nerdiest thing I’ve ever thought in earnest.

5:47: Earlier, from IM, re: rule changes protecting “defenseless” players:

Friend [11:45 AM]: probably don’t do very much to actually protect players

Friend [11:47 AM]: wouldn’t it be much more effective just to mandate equipment changes?

Friend [5:44 PM]: also, it would eliminate the alleged bias in those calls

So, the answer to this is so obviously “yes” that I’m interested in the second-order questions: 1) WTF is going on behind the scenes that has prevented this from happening? 2) What are the ulterior motives that we don’t know about—both on the owners’ and players’ sides?

5:52: Collinworth just said that we’ve seen more returns from deep in the endzone this season than ever before. First, I don’t know if that’s just his observation or if it’s based on actual stats. Second, even if it is based on real stats, I don’t know if he means in raw numbers or percentages—obv the first would be expected from the kickoff change. But—and it’s a big but—if teams actually were returning a higher percentage of kicks from deep in the endzone, wouldn’t THAT be interesting?

6:36: Can I interrupt this blog to say that I love my wife? Not only is she a great person, and a successful Harvard/Stanford educated lawyer, but she makes great spaghetti. Anyway, back from dinner. Working on a couple more graphs.

6:42: By the way, please email me any suggestions, ideas or opinions (positive or negative) you have about this live blog. Would you like to see more in-game analysis instead of game-inspired musing? More strict football and fewer tangents? More and broader tangents? More frequent and shorter updates or less frequent and more detailed? Etc. I kind of love doing it, so I’m set on it being a regular feature, and I’d obv like to do it the right way.

7:03: Cam Newton now has 1386 yards, which is the record for a rookie through his first 4 games (previously held by Marc Bulger with 1149). The record through 5 is 1496, so he’s likely to break that one. Through 6 is 1815, so that’s not a sure thing, but through 7 is also 1815 (Bulger only played 6 games, and the next highest at 7 is 1699). But there’s still a lot of variance to be navigated between now and Manning’s full-season record of 3739.

7:10: Aaron Schatz tweets:

FO_ASchatz

With all the wacky comebacks in the NFL this year, does anyone really want to write off the Jets this early?

1 minute ago

I’m sure he’s kidding, but I’m not sure “wacky comebacks” correlate much with “wacky comebacks.” Of course, a higher league-wide emphasis on passing will prob lead to more “comebacks” by previous standards: that is, games may be extended, there may be more turnovers, and trailing teams may have greater capability to catch up. But eventually this should just lead to a stasis where our perception of “wacky” changes: If a team has 10% chance of winning, they have a 10% chance of winning, whether that 10% means being behind 10 or being behind 20.

That said, under current league conditions, I’d say a 13 point lead definitely isn’t sufficient to “write off” any team that wasn’t DOA already.

7:33: Why does everyone call Romo “electrifying”? He had some “big” numbers on an offensive team, but what’s the evidence that any of that was his doing? Has he ever given the impression that he was doing more with his team than other quarterbacks would have?

7:39: Crap, my Excel just crashed and killed at least 15 minutes of work. Maybe not the best time to write my “Ode to spreadsheet software.” Though seriously, present resentments aside, isn’t Excel pretty much the best program ever?

7:42: And what the heck is it doing when it says “Excel is trying to recover your information. This may take several minutes.” This is a new(ish) computer. Nothing takes several minutes.

7:46: Matt notes:

I was just able to use the drive expectancy chart to check on a Chris Collinsworth comment, love all the graphs and tools. BTW the comment was about the value of getting the ball on the 2-3 vs the half yard line, if I read the graph right the odds of a safety double at the 1 yard line vs the three yard line. Still only 6% but a big enough difference to care.

Yes, there’s a significant difference between the two, and it gets more and more dramatic the closer you get to the plane: there’s a pretty significant difference from being at the 1 and being at the 1/2, etc. It’s also true on the other side of the field: all kinds of wacky things happen as you approach the Endzone, and they’re not all intuitive.

In fact, one of the big difficulties with building a WPA model is accounting for these kinds of situations empirically, because 1) they behave abnormally, and 2) they’re either rare (e.g., being right at your own end zone), or extremely specific (e.g., some of the things that happen around the 11-12 yard line in the Red Zone), and thus have some of the smallest sample sizes for observation.

7:51: Matt also asks:

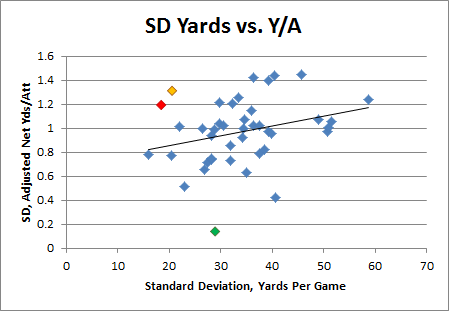

[I]n your salary research were there any trends dealing with the distribution of the players salary? Do winning teams generally have alot of average-paid players(The old New England Patriot teams) or alot of high paid elite players(Maybe the Colts? Cowboys? Not even sure what teams what qualify under this distinction.)

Yeah, this is actually closer to the main thing I’m interested in: E.g., what’s the most successful salary distribution profile? If you didn’t notice, the salary graph I posted last week actually has “Salary Standard Deviation” as a variable, so that gets at your question a little: Yes, it’s one of the most predictive indicators. However, a lot of that comes from quarterbacks: Since a few great quarterbacks (or at least quarterbacks on already-great teams) get enormous salaries, they’re kind of like automatic outliers.

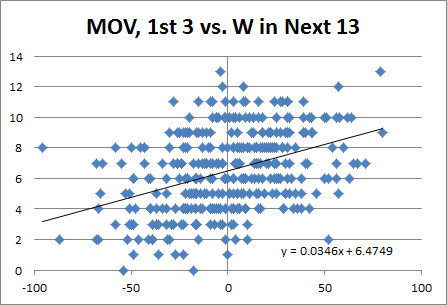

8:20: So, back to what I was working on before my Excel crashed: With all the turnovers in this game, there’s about a 100% chance that commentators later will talk about the importance of “turnover differential.” People always rattle off a bunch of stats about how the team that wins the “turnover battle” almost always wins the game (like, duh), with the intention of reminding everyone how terrible it is to take the kinds of risks that lead to turnovers.

But this causation goes both ways: Turnovers can obviously cause teams to lose, but teams losing also cause turnovers. When you’re behind, you have to take risks to have any chance of winning. Citing the “turnover battle” stats without context is about as ridiculous as citing the “team X is 43-1 when having a 100 yard rusher.”

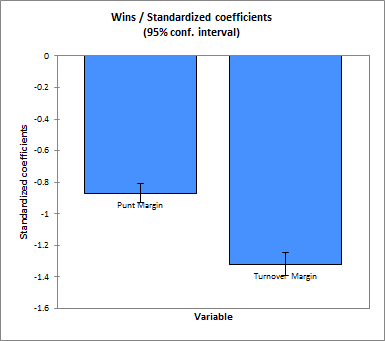

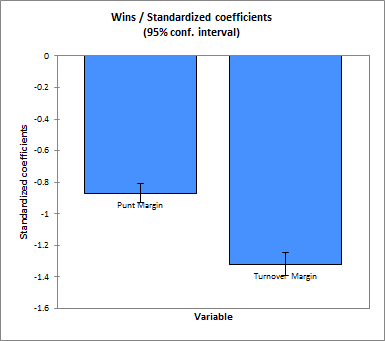

8:28: What goes unmentioned in all of this is “punt differential.” [Punts also involve turning the ball over.] Guess what? This stat is ALSO highly predictive of game outcomes, but without as much causation baggage: When teams are behind, they are actually forced to punt less. Despite the completely routine nature of punts vs. the extreme nature of turnovers, “punt differential” holds its own with “turnover differential” in a logistic regression to Win% (n=5308):

8:31: If you do run this as a linear regression to point differential, it gets even closer (I should also note, if you do your regression to “outside” games, punt differential is actually more predictive, but this is because it is much more reliable).

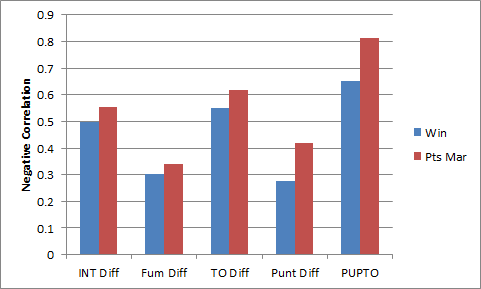

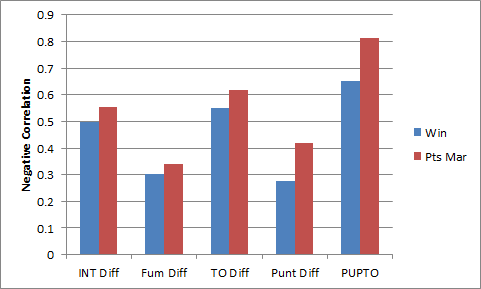

8:41: A fun metric that I love (and believe to be very useful) is “punts plus turnovers,” or PUPTO:

8:45: A pretty interesting thing to note in this chart is the difference between the predictivity of Interception differential vs. Fumble differential: from a pure “Turnovers=Bad” perspective, this is counter-intuitive: After all, many interceptions take place down-field, while fumbles typically happen at the line of scrimmage (also, I haven’t checked, but I feel like a disproportionate number of fumbles are returned for touchdowns). My suspicion is that this difference is at least partly explained by what I described earlier: When teams are losing, they have to take a lot of risks that lead to more interceptions, but they don’t take a lot of risks that lead to more fumbles.

8:51: Anyway, not seeing any more questions, I’m going to take off a few minutes early. Hope you enjoyed my blogging today, and I apologize for the technical difficulties. Cya.