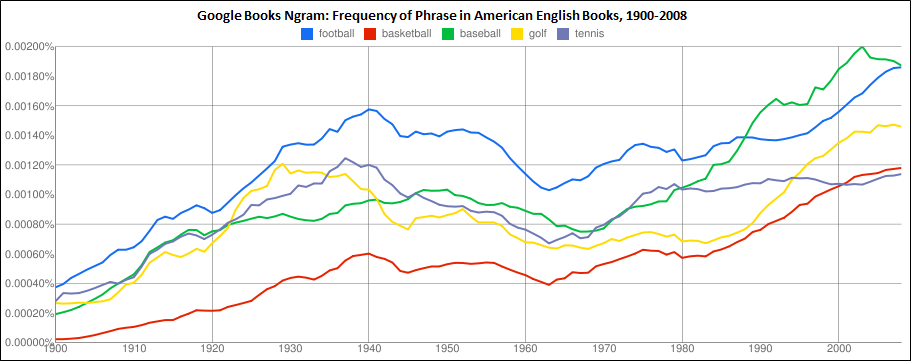

Does cash rule everything in professional sports? Obviously it keeps the lights on, and it keeps the best athletes in fine bling, but what effect does the root of all evil have on the competitive bottom line—i.e., winning championships?

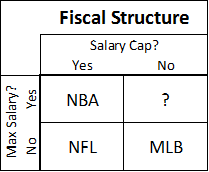

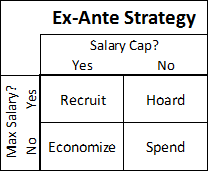

For this article, let’s consider “economically predictable” a synonym for “Cash Rules”: I will use extremely basic economic reasoning and just two variables—presence of a salary cap and presence of a salary max in a sport’s labor agreement—to establish, ex ante, which fiscal strategies we should expect to be the most successful. For each of the 3 major sports, I will then suggest (somewhat) testable hypotheses, and attempt to examine them. If the hypotheses are confirmed, then Method Man is probably right—dollar dollar bill, etc.

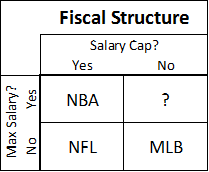

Conveniently, on a basic yes/no grid of these two variables, our 3 major sports in the U.S. fall into 3 different categories:

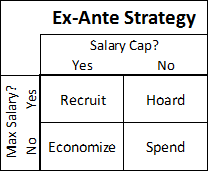

So before treating those as anything but arbitrary arrangements of 3 letters, we should consider the dynamics each of these rules creates independently. If your sport has a team salary cap, getting “bang for your buck” and ferreting out bargains is probably more important to winning than overall spending power. And if your sport has a low maximum individual salary, your ability to obtain the best possible players—in a market where everyone knows their value but must offer the same amount—will also be crucial. Considering permutations of thriftiness and non-economic acquisition ability, we end up with a simple ex ante strategy matrix that looks like this:

These one-word commandments may seem overly simple—and I will try to resolve any ambiguity looking at the individual sports below—but they are only meant to describe the most basic and obvious economic incentives that salary caps and salary maximums should be expected to create in competitive environments.

Major League Baseball: Spend

Hypothesis: With free-agency, salary arbitration, and virtually no payroll restrictions, there is no strategic downside to spending extra money. Combined with huge economic disparities between organizations, this means that teams that spend the most will win the most.

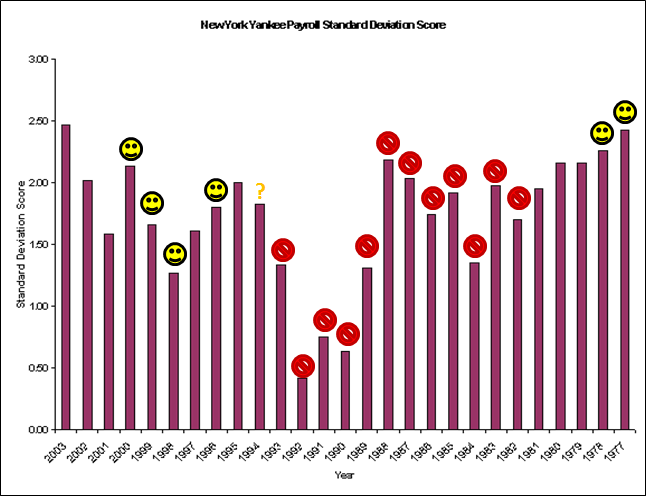

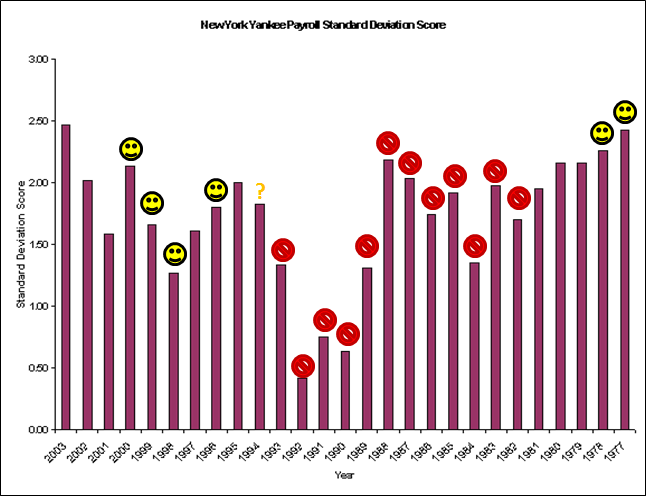

Analysis: Let’s start with the New York Yankees (shocker!), who have been dominating baseball since 1920, when they got Babe Ruth from the Red Sox for straight cash, homey. Note that I take no position on whether the Yankees filthy lucre is destroying the sport of Baseball, etc. Also, I know very little about the Yankees payroll history, prior to 1988 (the earliest the USA Today database goes). But I did come across this article from several years ago, which looks back as far as 1977. For a few reasons, I think the author understates the case. First, the Yankees low-salary period came at the tail end of a 12 year playoff drought (I don’t have the older data to manipulate, but I took the liberty to doodle on his original graph):

Note: Smiley-faces are Championship seasons. The question mark is for the 1994 season, which had no playoffs.

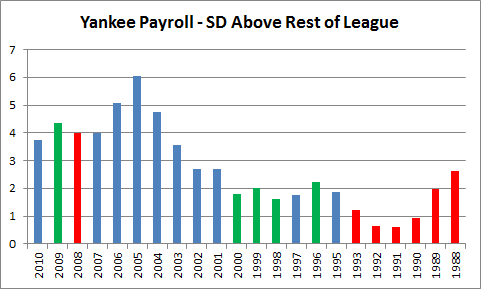

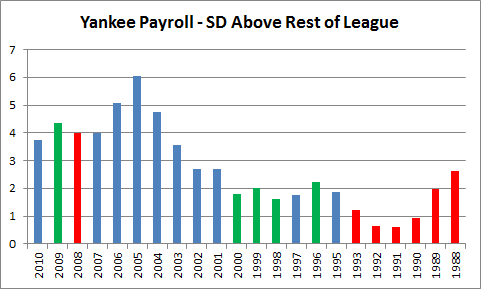

Also, as a quirk that I’ve discussed previously, I think including the Yankees in the sample from which the standard deviation is drawn can be misleading: they have frequently been such a massive outlier that they’ve set their own curve. Comparing the Yankees to the rest of the league, from last season back to 1988, looks like this:

Note: Green are Championship seasons. Red are missed playoffs.

In 2005 the rest-of-league average payroll was ~$68 million, and the Yankees’ was ~$208 million (the rest-of-league standard deviation was $23m, but including the Yankees, it would jump to $34m).

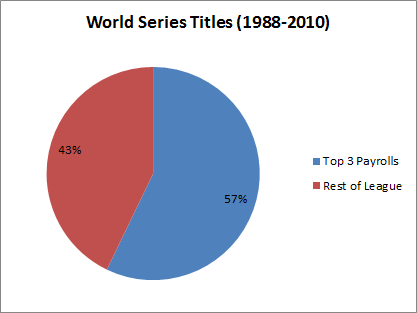

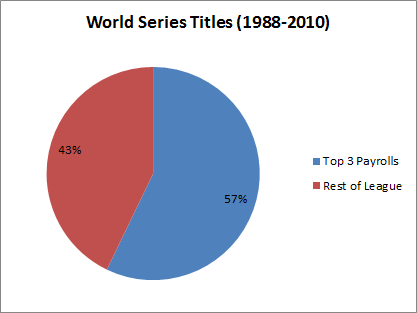

While they failed to win the World Series in some of their most expensive seasons, don’t let that distract you: money can’t guarantee a championship, but it definitely improves your chances. The Yankees have won roughly a quarter of the championships over the last 20 years (which is, astonishingly, below their average since the Ruth deal). But it’s not just them. Many teams have dramatically increased their payrolls in order to compete for a World Series title—and succeeded! Over the past 22 years, the top 3 payrolls (per season) have won a majority of titles:

As they make up only 10% of the league, this means that the most spendy teams improved their title chances, on average, by almost a factor of 6.

National Basketball Association: Recruit (Or: “Press Your Bet”)

Hypothesis: A fairly strict salary cap reigns in spending, but equally strict salary regulations mean many teams will enjoy massive surplus value by paying super-elite players “only” the max. Teams that acquire multiple such players will enjoy a major championship advantage.

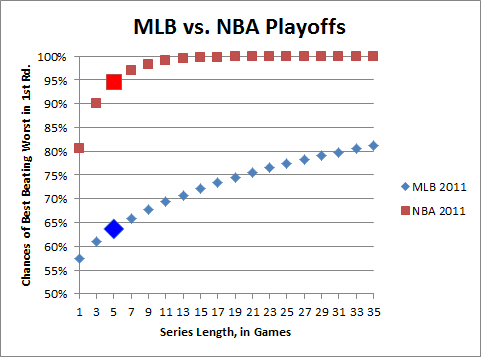

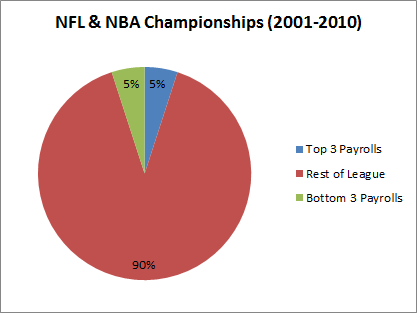

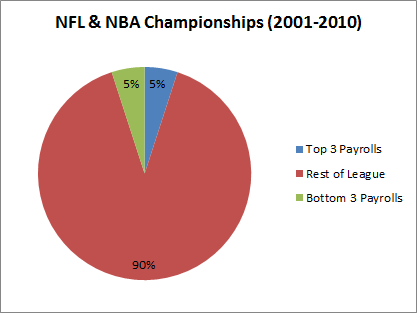

Analysis: First, in case you were thinking that the 57% in the graph above might be caused by something other than fiscal policy, let’s quickly observe how the salary cap kills the “spend” strategy:

Payroll information from USA Today’s NBA and NFL Salary Databases (incidentally, this symmetry is being threatened, as the Lakers, Magic, and Mavericks have the top payrolls this season).

I will grant there is a certain apples-to-oranges comparison going on here: the NFL and NBA salary-cap rules are complex and allow for many distortions. In the NFL teams can “clump” their payroll by using pro-rated signing bonuses (essentially sacrificing future opportunities to exceed the cap in the present), and in the NBA giant contracts are frequently moved to bad teams that want to rebuild, etc. But still: 5%. Below expectation if championships were handed out randomly.

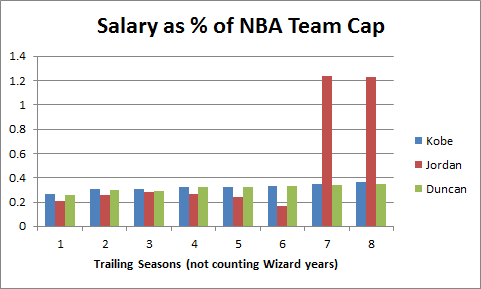

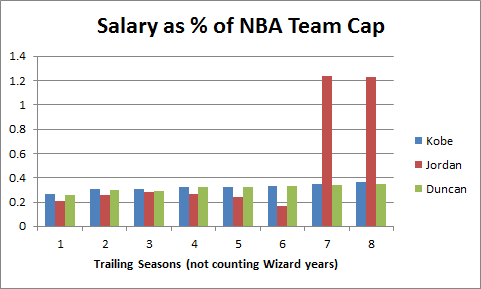

And basketball championships are NOT handed out randomly. My hypothesis predicts that championship success will be determined by who gets the most windfall value from their star player(s). Fifteen of the last 20 NBA championships have been won by Kobe Bryant, Tim Duncan, or Michael Jordan. Clearly star-power matters in the NBA, but what role does salary play in this?

Prior to 1999, the NBA had no salary maximum, though salaries were regulated and limited in a variety of ways. Teams had extreme advantages signing their own players (such as Bird rights), but lack of competition in the salary market mostly kept payrolls manageable. Michael Jordan famously signed a lengthy $25 million contract extension basically just before star player salaries exploded, leaving the Bulls with the best player in the game for a song (note: Hakeem Olajuwon’s $55 million payday came after he won 2 championships as well). By the time the Bulls were forced to pay Jordan his true value, they had already won 4 championships and built a team around him that included 2 other All-NBA caliber players (including one who also provided extreme surplus value). Perhaps not coincidentally, year 6 in the graph below is their record-setting 72-10 season:

Note: Michael Jordan’s salary info found here. Historical NBA salary cap found here.

The star player salary situation caught the NBA off-guard. Here’s a story from Time magazine in 1996 that quotes league officials and executives:

“It’s a dramatic, strategic judgment by a few teams,” says N.B.A. deputy commissioner Russ Granik. .

Says one N.B.A. executive: “They’re going to end up with two players making about two-thirds of the salary cap, and another pair will make about 20%. So that means the rest of the players will be minimum-salary players that you just sign because no one else wants them.” . . .

Granik frets that the new salary structure will erode morale. “If it becomes something that was done across the league, I don’t think it would be good for the sport,” he says.

What these NBA insiders are explaining is basic economics: Surprise! Paying better players big money means less money for the other guys. Among other factors, this led to 2 lockouts and the prototype that would eventually lead to the current CBA (for more information than you could ever want about the NBA salary cap, here is an amazing FAQ).

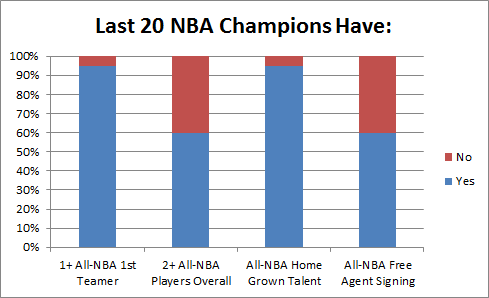

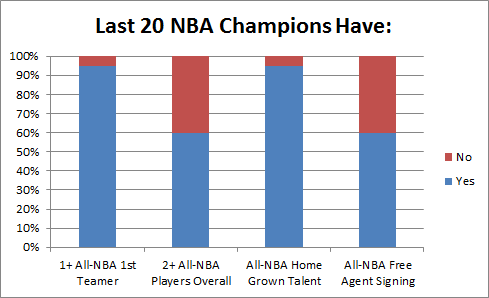

The fact that the best players in the NBA are now being underpaid relative to their value is certain. As a back of the envelope calculation: There are 5 players each year that are All-NBA 1st team, while 30+ players each season are paid roughly the maximum. So how valuable are All-NBA 1st team players compared to the rest? Let’s start with: How likely is an NBA team to win a championship without one?

In the past 20 seasons, only the 2003-2004 Detroit Pistons won the prize without a player who was a 1st-Team All-NBAer in their championship year.

To some extent, these findings are hard to apply strategically. All but those same Pistons had at least one home-grown All-NBA (1st-3rd team) talent—to win, you basically need the good fortune to catch a superstar in the draft. If there is an actionable take-home, however, it is that most (12/20) championship teams have also included a second All-NBA talent acquired through trade or free agency: the Rockets won after adding Clyde Drexler, the second Bulls 3-peat added Dennis Rodman (All-NBA 3rd team with both the Pistons and the Spurs), the Lakers and Heat won after adding Shaq, the Celtics won with Kevin Garnett, and the Lakers won again after adding Pau Gasol.

Each of these players was/is worth more than their market value, in most cases as a result of the league’s maximum salary constraints. Also, in most of these cases, the value of the addition was well-known to the league, but the inability of teams to outbid each other meant that basketball money was not the determinant factor in the players choosing their respective teams. My “Recruit” strategy anticipated this – though it perhaps understates the relative importance of your best player being the very best. This is more a failure of the “recruit” label than of the ex ante economic intuition, the whole point of which was that cap+max –> massive importance of star players.

National Football League: Economize (Or: “WWBBD?”)

Hypothesis: The NFL’s strict salary cap and lack of contract restrictions should nullify both spending and recruiting strategies. With elite players paid closer to what they are worth, surplus value is harder to identify. We should expect the most successful franchises to demonstrate both cunning and wise fiscal policy.

Analysis: Having a cap and no max salaries is the most economically efficient fiscal design of any of the 3 major sports. Thus, we should expect that massively dominating strategies to be much harder to identify. Indeed, the dominant strategies in the other sports are seemingly ineffective in the NFL: as demonstrated above, there seems to be little or no advantage to spending the most, and the abundant variance in year-to-year team success in the NFL would seem to rule out the kind of individual dominance seen in basketball.

Thus, to investigate whether cunning and fiscal sense are predominant factors, we should imagine what kinds of decisions a coach or GM would make if his primary qualities were cunning and fiscal sensibility. In that spirit, I’ve come up with a short list of 5 strategies that I think are more or less sound, and that are based largely on classically “economic” considerations:

1. Beg, borrow, or steal yourself a great quarterback:

Superstar quarterbacks are probably underpaid—even with their monster contracts—thus making them a good potential source for surplus value. Compare this:

Note: WPA (wins added) stats from here.

With this:

The obvious caveat here is that the entanglement question is still empirically open: How much do good QB’s make their teams win v. How much do winning teams make their QB’s look good? But really quarterbacks only need to be responsible for a fraction of the wins reflected in their stats to be worth more than what they are being paid. (An interesting converse, however, is this: the fact that great QB’s don’t win championships with the same regularity as, say, great NBA players, suggests that a fairly large portion of the “value” reflected by their statistics is not their responsibility).

2. Plug your holes with the veteran free agents that nobody wants, not the ones that everybody wants:

If a popular free agent intends to go to the team that offers him the best salary, his market will act substantially like a “common value” auction. Thus, beware the Winner’s Curse. In simple terms: If 1) a player’s value is unknown, 2) each team offers what they think the player is worth, and 3) each team is equally likely to be right; then: 1) The player’s expected value will correlate with the average bid, and 2) the “winning” bid probably overpaid.

Moreover, even if the winner’s bid is exactly right, that just means they will have successfully gained nothing from the transaction. Assuming equivalent payrolls, the team with the most value (greatest chance of winning the championship) won’t be the one that pays the most correct amount for its players, it will—necessarily—be the one that pays the least per unit of value. To accomplish this goal, you should avoid common value auctions as much as possible! In free agency, look for the players with very small and inefficient markets (for which #3 above is least likely to be true), and then pay them as little as you can get away with.

3. Treat your beloved veterans with cold indifference.

If a player is beloved, they will expect to be paid. If they are not especially valuable, they will expect to be paid anyway, and if they are valuable, they are unlikely to settle for less than they are worth. If winning is more important to you than short-term fan approval, you should be both willing and prepared to let your most beloved players go the moment they are no longer a good bargain.

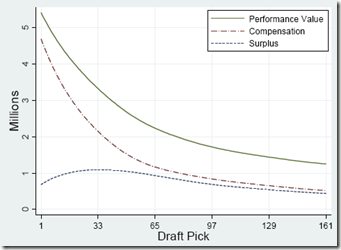

4. Stock up on mid-round draft picks.

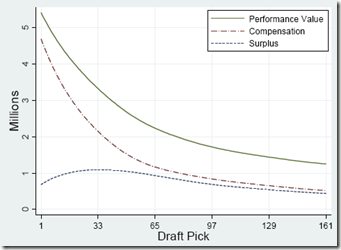

Given the high cost of signing 1st round draft picks, 2nd round draft picks may actually be more valuable. Here is the crucial graph from the Massey-Thaler study of draft pick value (via Advanced NFL Stats):

The implications of this outcome are severe. All else being equal, if someone offers you an early 2nd round draft pick for your early 1st round draft pick, they should be demanding compensation from you (of course, marginally valuable players have diminishing marginal value, because you can only have/play so many of them at a time).

5. When the price is right: Gamble.

This rule applies to fiscal decisions, just as it does to in-game ones. NFL teams are notoriously risk-averse in a number of areas: they are afraid that someone after one down season is washed up, or that an outspoken player will ‘disrupt’ the locker room, or that a draft pick might have ‘character issues’. These sorts of questions regularly lead to lengthy draft slides and dried-up free agent markets. And teams are right to be concerned: these are valid possibilities that increase uncertainty. Of course, there are other possibilities. Your free agent target simply may not be as good as you hope they are, or your draft pick may simply bust out. Compare to late-game 4th-down decisions: Sometimes going for it on 4th down will cause you to lose immediately and face a maelstrom of criticism from fans and press, where punting or kicking may quietly lead to losing more often. Similarly, when a team takes a high-profile personnel gamble and it fails, they may face a maelstrom of criticism from fans and press, where the less controversial choice might quietly lead to more failure.

The economizing strategy here is to favor risks when they are low cost but have high upsides. In other words, don’t risk a huge chunk of your cap space on an uncertain free agent prospect, risk a tiny chunk of your cap space on an even more uncertain prospect that could work out like gangbusters.

Evaluation:

Now, if only there were a team and coach dedicated to these principles—or at least, for contrapositive’s sake, a team that seemed to embrace the opposite.

Oh wait, we have both! In the last decade, Bill Belichick and the New England Patriots have practically embodied these principles, and in the process they’ve won 3 championships, have another 16-0/18-1 season, have set the overall NFL win-streak records, and are presently the #1 overall seed in this year’s playoffs. OTOH, the Redskins have practically embodied the opposite, and they have… um… not.

Note that the Patriots’ success has come despite a league fiscal system that allows teams to “load up” on individual seasons, distributing the cost onto future years (which, again, helps explain the extreme regression effect present in the NFL). Considering the long odds of winning a Super Bowl—even with a solid contender—this seems like an unwise long-run strategy, and the most successful team of this era has cleverly taken the long view throughout.

Conclusions

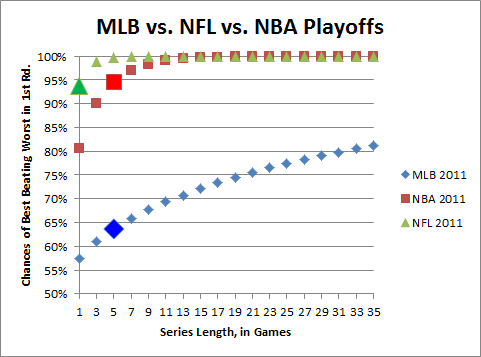

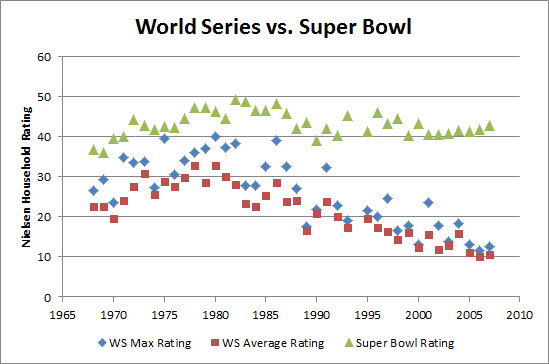

The evidence in MLB and in the NBA is ironclad: Basic economic reasoning is extremely probative when predicting the underlying dynamics behind winning titles. Over the last 20 years of pro baseball, the top 3 spenders in the league each year win 57% of the championships. Over a similar period in basketball, the 5 (or fewer) teams with 1st-Team All-NBA players have won 95%.

In the NFL, the evidence is more nuance and anecdote than absolute proof. However, our ex ante musing does successfully predict that neither excessive spending nor recruiting star players at any cost (excepting possibly quarterbacks) is a dominant strategy.

On balance, I would say that the C.R.E.A.M. hypothesis is substantially more supported by the data than I would have guessed.

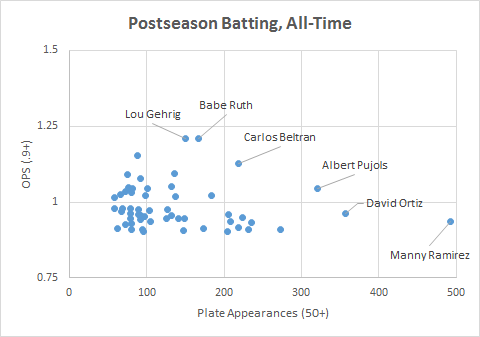

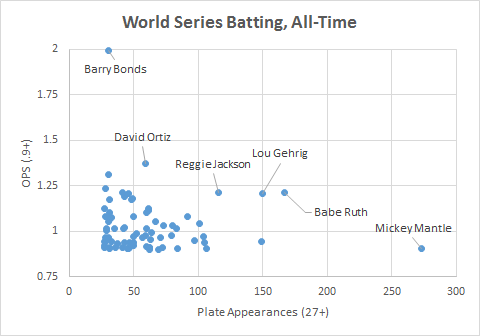

By my reading, Ortiz fits clearly in an elite class of outliers that includes Bonds, Jackson, Gehrig and Ruth, though Ruth stands out the most. Note that this includes Ruth’s first three WS appearances with Boston, when he was still a pitcher. I.e.:

By my reading, Ortiz fits clearly in an elite class of outliers that includes Bonds, Jackson, Gehrig and Ruth, though Ruth stands out the most. Note that this includes Ruth’s first three WS appearances with Boston, when he was still a pitcher. I.e.: