[Note: I apologize for missing last Wednesday and Friday in my posting schedule. I had some important business-y things going on Wed and then went to Canada for a wedding over the weekend.]

Last week I came across this ESPN article (citing this Forbes article) about how Bill Belichick is the highest-paid coach in American sports:

Bill Belichick tops the list for the second year in a row following the retirement of Phil Jackson, the only coach to have ever made an eight-figure salary. Belichick is believed to make $7.5 million per year. Doc Rivers is the highest-paid NBA coach at $7 million.

Congrats to Belichick for a worthy accomplishment! Though I still think it probably under-states his actual value, at least relative to NFL players. As I tweeted:

Alternate headline: Bill Belichick Still Woefully Underpaid m.espn.go.com/general/blogs/…

— Benjamin Morris (@skepticalsports) May 23, 2012

Of course, coaches’ salaries are different from players’: they aren’t constrained by the salary cap, nor are they boosted by the mandatory revenue-sharing in the players’ collective bargaining agreement. Yet, for comparison, this season Belichick will make a bit more than a third of what Peyton Manning will in Denver. As I’ve said before, I think Belichick and Manning have been (almost indisputably) the most powerful forces in the modern NFL (maybe ever). Here’s the key visual from my earlier post, updated to include last season (press play):

The x axis is wins in season n, y axis is wins in season n+1.

Naturally, Belichick has benefited from having Tom Brady on his team. However, Brady makes about twice as much as Belichick does, and I think you would be hard-pressed to argue that he’s twice as valuable—and I think top QB’s are probably underpaid relative to their value anyway.

But being high on Bill Belichick is about more than just his results. He is well-loved in the analytical community, particularly for some of his high-profile 4th down and other in-game tactical decisions. But I think those flashy calls are merely a symptom of his broader commitment to making intelligent win-maximizing decisions—a commitment that is probably even more evident in the decisions he has made and strategies he has pursued in his role as the Patriots’ General Manager.

But rather than sorting through everything Belichick has done that I like, I want to take a quick look at one recent adjustment that really impressed me: the Patriots out-of-character machinations in the 2012 draft.

The New Rookie Salary Structure

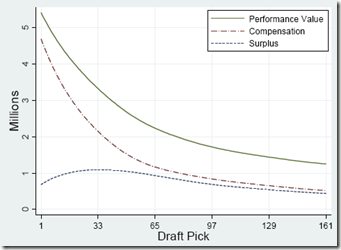

One of the unheralded elements to the Patriots’ success—perhaps rivaling Tom Brady himself in actual importance—is their penchant for stock-piling draft-picks in the “sweet spot” of the NFL draft (late 1st to mid-2nd round), where picks have the most surplus value. Once again, here’s the killer graph from the famous Massey-Thaler study on the topic:

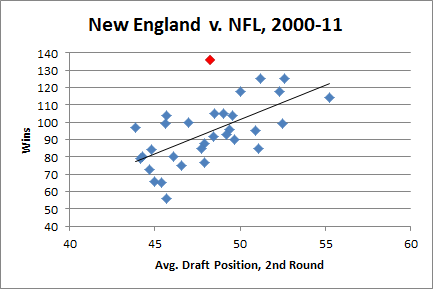

In the 11 drafts since Belichick took over, the Patriots have made 17 picks between numbers 20 and 50 overall, the most in the NFL (the next-most is SF with 15, league average is obv 11). To illustrate how unusual their draft strategy has been, here’s a plot of their 2nd round draft position vs. their total wins over the same period:

Despite New England having the highest win percentage (not to mention most Super Bowl wins and appearances) over the period, there are 15 teams with lower average draft positions in the 2nd round. For comparison, they have the 2nd lowest average draft position in the 1st round and 7th lowest in the third.

Of course, the new collective bargaining agreement includes a rookie salary scale. Without going into all the details (in part because they’re extremely complicated and not entirely public), the key points are that it keeps total rookie compensation relatively stable while flattening the scale at the top, reducing guaranteed money, and shortening the maximum number of years for each deal.

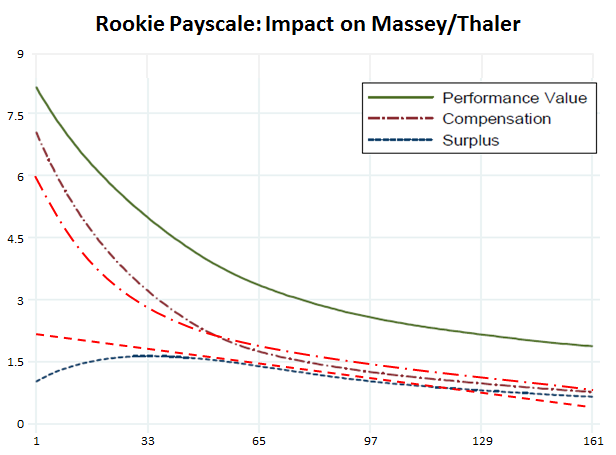

These changes should all theoretically flatten out the “value curve” above. Here’s a rough sketch of what the changes seem to be attempting:

Since the original study was published, the dollar values have gone up and the top end has gotten more skewed. I adjusted the Y-axis to reflect the new top, but didn’t adjust the curve itself, so it should actually be somewhat steeper than it appears. I tried to make the new curves as conceptually accurate as I could, but they’re not empirical and should be considered more of an “artist’s rendition” of what I think the NFL is aiming for.

With a couple of years of data, this should be a very interesting issue to revisit. But, for now, I think it’s unlikely that the curve will actually be flattened very much. If I had to guess, I think it may end up “dual-peaked”: By far the greatest drop in guaranteed money will be for top QB prospects taken with the first few picks. These players already provide the most value, and are the main reason the original M/T performance graph inclines so steeply on the left. Additionally, they provide an opportunity for continued surplus value beyond the length of the initial contract. This should make the top of the draft extremely attractive, at least in years with top QB prospects.

On the other hand, I think the bulk of the effect on the rest of the surplus-value curve will be to shift it to the left. My reasons for thinking this are much more complicated, and include my belief that the original Massey/Thaler study has problems with its valuation model, but the extremely short version is that I have reason to believe that people systematically overvalue upper/middle 1st round picks.

How the Patriots Responded

Since I’ve been following the Patriots’ 2nd-round-oriented drafting strategy for years now, naturally my first thoughts after seeing the details of the new deal went to how this could kill their edge. Here’s a question I tweeted at the Sloan conference:

For Football panel: Is new CBA going to hurt the Patriots, who built a dynasty partly by fleecing the league w 2nd round draft picks? #SSAC

— Benjamin Morris (@skepticalsports) March 3, 2012

Actually, my concern about the Patriots drafting strategy was two-fold:

- The Patriots favorite place to draft could obviously lose its comparative value under the new system. If they left their strategy as-is, it could lead to their picking sub-optimally. At the very least, it should eliminate their exploitation opportunity.

- Though a secondary issue for this post, at some point taking an extreme bang-for-your-buck approach to player value can run into diminishing returns and cause stagnation. Since you can only have so many players on your roster or on the field at a time, your ability to hoard and exploit “cheap” talent is constrained. This is a particularly big concern for teams that are already pretty good, especially if they already have good “value” players in a lot of positions: At some point, you need players who are less cheap but higher quality, even if their value per dollar is lower than the alternative.

Of course, if you followed the draft, you know that the Patriots, entering the draft with far fewer picks than usual, still traded up in the 1st round, twice.

Taken out of context, these moves seem extremely out of character for the Patriots. Yet the moves are perfectly consistent with an approach that understands and attacks my concerns: Making fewer, higher-quality picks is essentially the correct solution, and if the value-curve has indeed shifted up as I expect it has, the new epicenter of the Patriots’ draft activity may be directly on top of the new sweet spot.

Baseball

The entire affair reminds me of an old piece of poker wisdom that goes something like this: In a mixed game with one truly expert poker player and a bunch of completely outclassed amateurs, the expert’s biggest edge wouldn’t come in the poker variant with which he has the most expertise, but in some ridiculous spontaneous variant with tons of complicated made-up rules.

I forget where I first read the concept, but I know it has been addressed in various ways by many authors, ranging from Mike Caro to David Sklansky. I believe it was the latter (though please correct me if I’m wrong), who specifically suggested a Stud variant some of us remember fondly from childhood:

Several different games played only in low-stakes home games are called Baseball, and generally involve many wild cards (often 3s and 9s), paying the pot for wild cards, being dealt an extra upcard upon receiving a 4, and many other ad-hoc rules (for example, the appearance of the queen of spades is called a “rainout” and ends the hand, or that either red 7 dealt face-up is a rainout, but if one player has both red 7s in the hole, that outranks everything, even a 5 of a kind). These same rules can be applied to no peek, in which case the game is called “night baseball”.

The main ideas are that A) the expert would be able to adapt to the new rules much more quickly, and B) all those complicated rules make it much more likely that he would be able to find profitable exploitations (for Baseball in particular, there’s the added virtue of having several betting rounds per hand).

It will take a while to see how this plays out, and of course the abnormal outcome could just be a circumstances-driven coincidence rather than an explicit shift in the Patriots’ approach. But if my intuitions about the situation are right, Belichick may deserve extra credit for making deft adjustments in a changing landscape, much as you would expect from the Baseball-playing shark.